This post links to a fuzzing project for sqlite3, explaining my approach and implementation to fuzz sqlite3 sort of effectively.

Implementation and approach

Status quo

While fuzz testing could basically manifest as input generation, measurement of coverage and post-stage validation on crashes, the high level of maturity of modern database systems poses a big challenge in this process, since a huge number of ubiquitous memory corruption bugs have been fixed up by developers and these systems in turn become fairly resistant to this type of bugs.

Additionally, an invalid input usualy fails passing early validity checking, and hardly reaches to code snippets inhabiting in the deep application logic. The only approach to effectively accomplishing significantly high code coverage is to generate as more valid inputs as a fuzzer can. Another problem towards effectiveness is persistency of database systems. At the starting point, a system is in an empty state, without storing any user data, in which performing operations, such as query and deletion will not reach to the meaningful code logic. Hence, it is necessary to consider testing of different types of interfaces in order. For instance, we need to fill a system with a tons of valid user data before start testing on query commands.

In order to generate valid inputs accepted by testing targets, a good fuzzer should conform satisfiable input generation in structure. The next section will cover more detail.

Coverting syntax diagrams for sqlite3 to a Python-resolvable grammar

How does a grammar-based fuzzer generate an input? Basically, a grammar should be defined such that the fuzzer could make use of this grammar to generate and mutate an input.

According to fuzzing with grammars, an example grammar looks like:

EXPR_GRAMMAR: Grammar = {

"<start>":

["<expr>"],

"<expr>":

["<term> + <expr>", "<term> - <expr>", "<term>"],

"<term>":

["<factor> * <term>", "<factor> / <term>", "<factor>"],

"<factor>":

["+<factor>",

"-<factor>",

"(<expr>)",

"<integer>.<integer>",

"<integer>"],

"<integer>":

["<digit><integer>", "<digit>"],

"<digit>":

["0", "1", "2", "3", "4", "5", "6", "7", "8", "9"]

}

Relying on such a structure, the fuzzer could concretize an input from abstract symbols to actual digits or characters.

There are quite a few diagrams to elaborate on sqlite3 grammars as defined in its official website. Even though they are prone to be human-readable, a grmmar-based fuzzer can not resolve such a complex grammar without flattening it down to a machine-understandable structure.

Constraining its grammar

As soon as we finalize the grammar for sqlite3, the fuzzer is being capable of emmiting sort of inputs. However, are these inputs taken by the running sqlite3 program, leading to acceptable coverage? Actually, you should have seen a low coverage rate mainly because these previously generated inputs were dealt with as “trash” data, hardly reaching to the deep application logic of their corresponding input handlers. For example, the fuzzer in such a situation may generate an invalid command to create a table of four columns by providing 5 columns of initial inputs.

According to these low results, we need to adopt some constraints on the grammar, forcing the fuzzer to consider the current context while concretizing each symbol.

In the chapter Fuzzing with Generators of fuzzing book, fuzzing with generators hold a similar idea to a hook function, executing a function to sanitize data before/after one symbol being processed. Let us take creation and detachment of a database as an example:

grammar = {

"<start>": [

"<create_database>",

"<detach_stmt>"

],

'<create_database>':[

(' ', opts(pre=lambda: "CREATE DATABASE " + random.choice(OPTIONAL_DATABASE) + ";")),

],

'<detach_stmt>':[

(' ', opts(pre=lambda: "DETACH DATABASE " + random.choice(OPTIONAL_DATABASE) + ";")),

],

...

}

Here, it can be seen in a way that all of database names come from a pre-define list, and in turn detachment commands will be generated according to that list, such that there is a high chance that sqlite3 could detach a database that has been previously created. This is why we need some constraints, leading input generation towards validity. Cool, once we are carefully done with a bunch of setting of constraints, we could see a huge boost in branch coverage.

Arranging various fuzzing stages (statefulness)

Until now, the fuzzer seems working out, generating valid inputs with the help of applied constraints. However, database is quite a complex software program that maintains a lot of states while running. If we strive for much higher branch coverage, guiding sqlite3 into a crafted context is a good approach to meet an increase. In other words, we need to prepare sqlite being in a state we expect by feeding different types of input in an order. For my implementation, all commands are divided into four stages, e.g., init state involves creation of table, trigger, view, index, cte, virtual table, and json stmt.

First three rounds of fuzz testing manifest as:

- init (0~3000 inputs)

- busy (3000~8000 inputs)

- post (8000~10000 inputs)

Then the preceeding two rounds of testing are shown as below:

- bruteforce (0~3000 inputs)

- misc (3000~10000 inputs)

Furthermore, after five rounds, this process starts over.

Thanks to such a structure of input generation, we could more or less retain statefulness, considering dependency between those commands. Similarly, fuzzing network protocols also requires stateful input organization, leading to our desire states for testing from the starting point.

Beware that each stage in a round ties into different perspectives and someone may consider more inputs in any of these stages or propose a more grained stage.

Introducing more contraints by referring to coverage report

Once the fuzz testing is done, a coverage report that details whether a function is executed is generated. One could attempt to improve his grammar or apply more constraints in the grammar to reach these missed-out functions.

Evaluation results

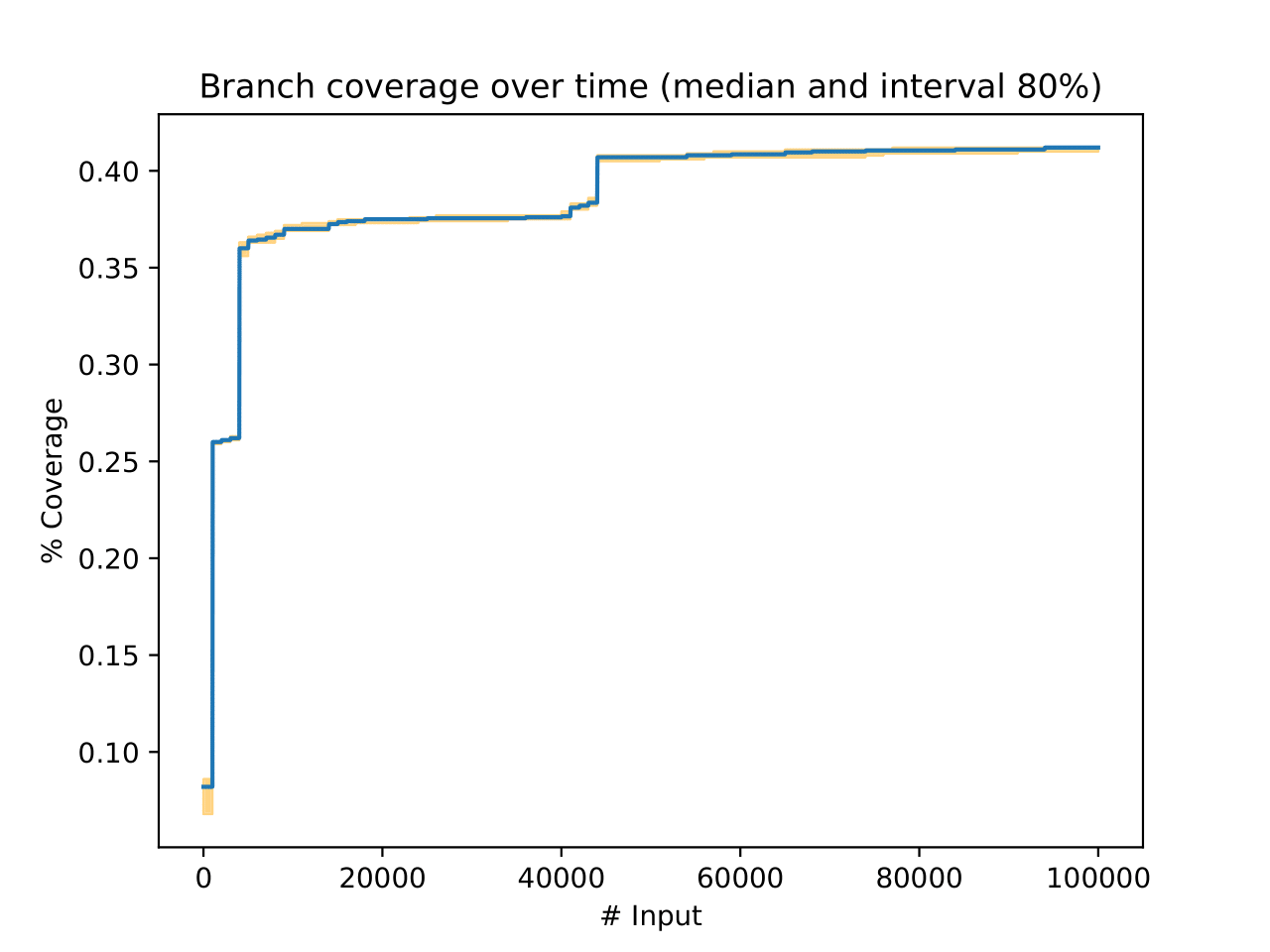

.

.

This diagram consists of a blue line and orange-covered areas. The blue line represents median values for n rounds of experiment, while the orange zones indicate the low and upper bounds for these median values. This is to say, given a certain confidence level, we could how stable each experiment could be in terms of growth of branch coverage.

As the evaluation diagram illustrated, the branch coverage reaches to roughly 36% as soon as three rounds of input have been generated.

Following these, the branch coverage sees a boost, rising to approximately 41% after two rounds of bruteforce and misc states.

Finally, we could see this in a way that the shadow area represents 80% interval, indicating nearly no difference in branch coverage of all testing.

Improvement - inspect which function has not been covered

Additionally, it is interesting to cover those functions that require a complex and dedicated combination of commands for reach, e.g., memory management functions. As far as I know from previous coverage reports, there is a certainly significant number of memory-related functions that have not been covered.